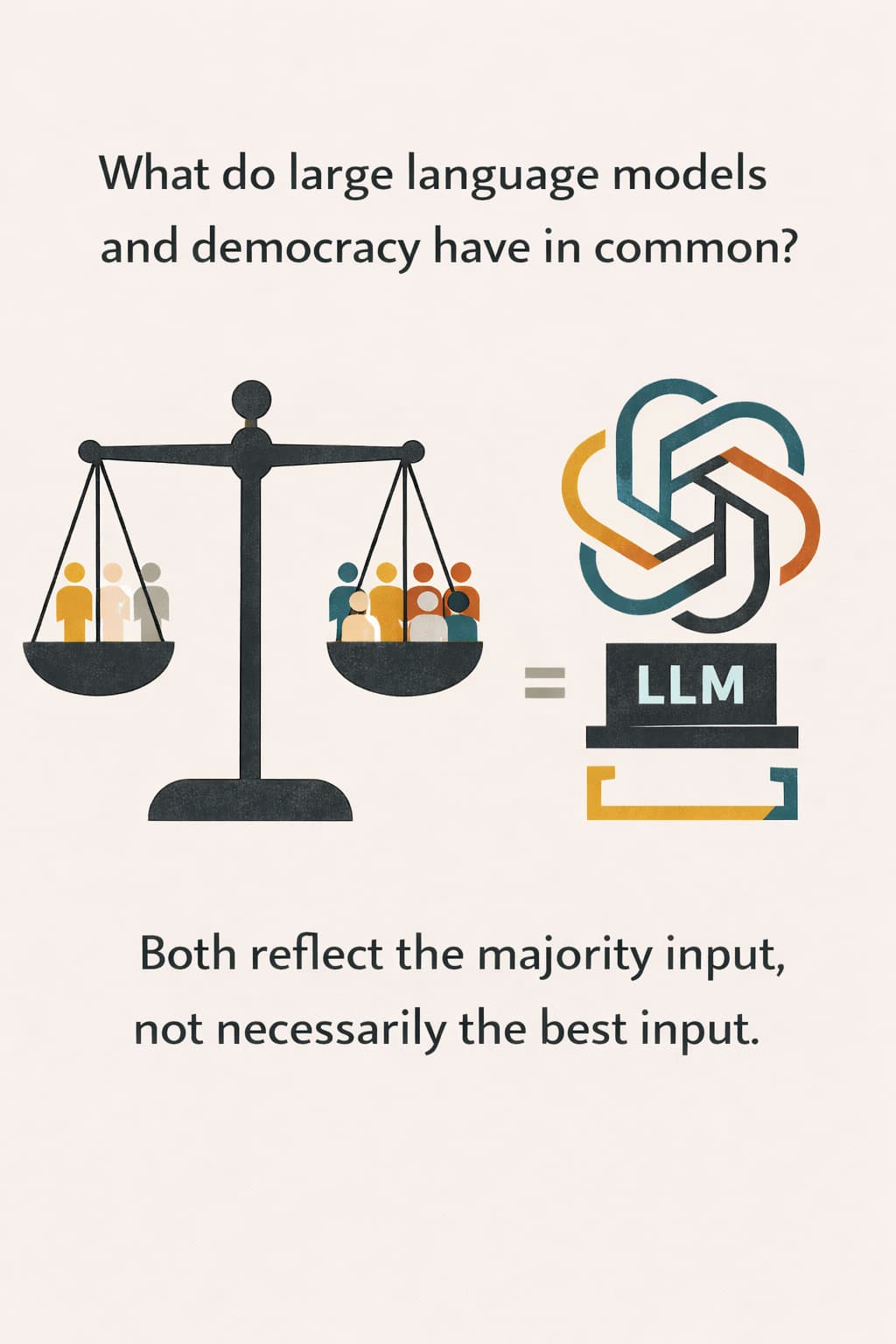

What do large language models and democracy have in common?

More than you’d expect.

The other day, I was trying to set up a JIRA automation and asked ChatGPT for help. I even handed it a direct link to the official documentation. Still, the answer was confidently wrong. Not “close but off”—just plain wrong. It had been trained on so much outdated or incorrect data that even a primary source couldn’t sway it.

That’s when it hit me: LLMs and democracies both reflect the majority input, not necessarily the best input. If most of the content out there is noisy, messy, or just plain wrong… well, that’s what the model learns from. And let’s face it—there’s more bad code and mediocre Stack Overflow threads than clean, well-tested engineering wisdom.

So when people write software using AI today, especially in what I call vibe coding mode (a.k.a. “it compiles, must be fine”), it often works until something real happens—like a new use case, a weird user input, or daylight savings. Then it all falls apart.

Yes, agents and validators can patch the holes. But if the foundation is shaky, you’ll spend more time firefighting than building. Maybe we should ask: are we training systems to reflect the world as it is, or as it should be?